UK funding streams for zero emission buses, well explained

A combination of government funds with investment from local authorities and operators is the UK’s approach to the zero emissions transition. However, ensuring patronage is the key to long term viability

Below, an article published on February 2023 issue of Sustainable Bus magazine.

By Alex Byles

In the UK, consultation on the end date on the sale of new, non-zero emission buses, currently proposed between 2025 and 2032, is ongoing. To incentivise the transition, so far, the UK’s Department for Transport (DfT) has invested £320m (€362m) towards the goal of funding 4,000 zero emission (ZE) buses in service by 2025.

Investment to support the ZE transition is also required from regional transport authorities and operators, where the UK model largely consists of private operators, dominated by five primary companies (Arriva, FirstGroup, Go-Ahead, National Express, Stagecoach), running services on behalf of local government authorities. However, a trend of declining revenue from lower passenger numbers across most regions is a challenge

With 1,724 ZE buses in operation in the UK by October last year amongst a total fleet of 37,800, and approximately half of the UK’s current ZE buses operating in London alone, over 95% of the UK’s vehicles are still to transition.

As ZEBRA has comprised rounds of application and competition for funding at intervals, this has also created uncertainty and a stop-start procurement approach. Tim Griffen, project officer at Zemo Partnership, says: “Operators and local authorities work hard to compete for a share of government funding announced at intervals, then there’s a delay before the money is actually received, then there’s a rush to the manufacturer. And, if the application is unsuccessful, they may not receive any funding”.

Grants and incentives

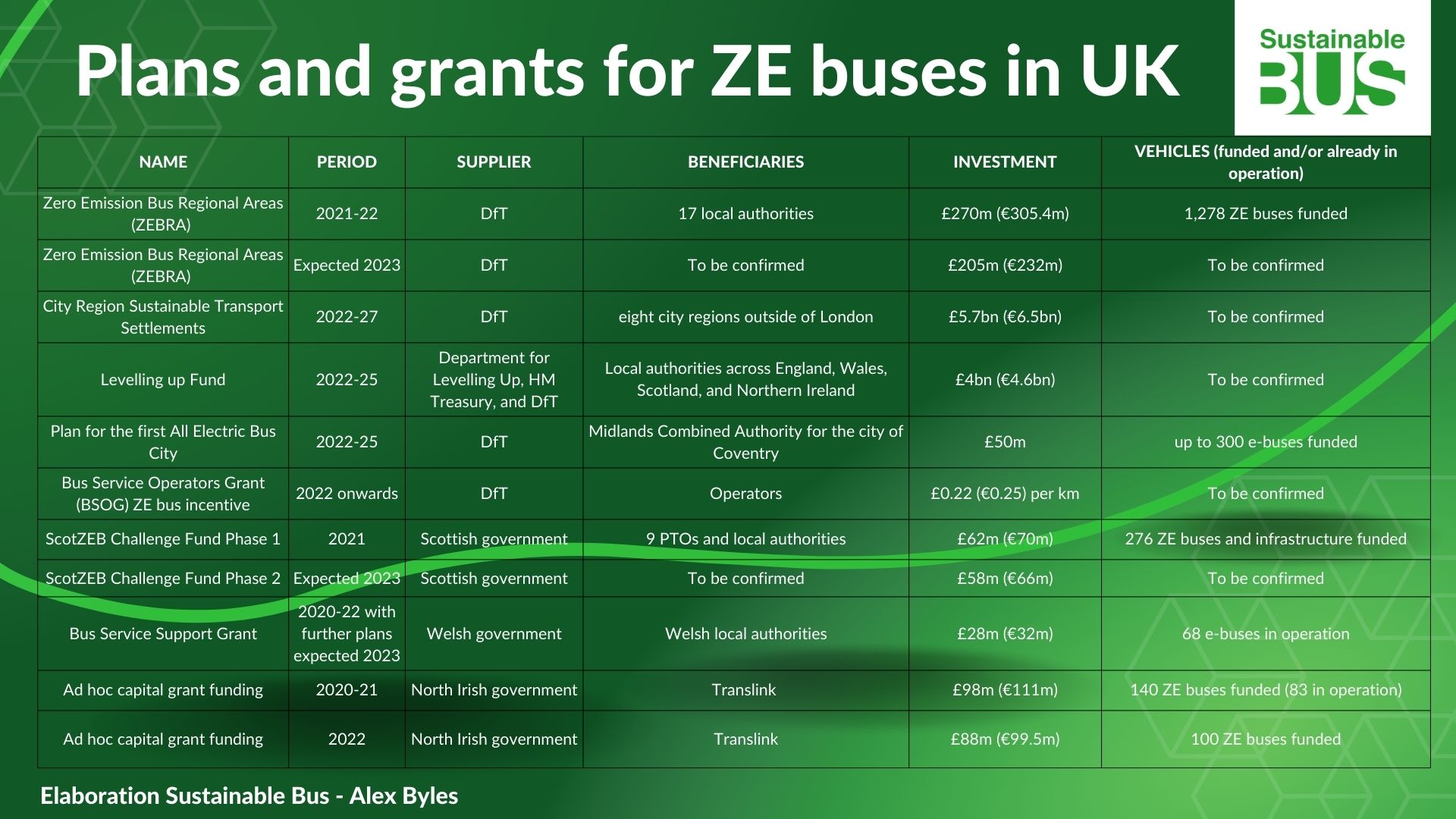

In England, excluding London, the DfT has awarded competition-based grants to local authorities, most recently comprising the Zero Emission Bus Regional Areas (ZEBRA) scheme. This has distributed £270m (€305.4m) in 2021/22 to 17 local authorities, with a further £205m (€232m) to be issued this year. ZEBRA application is competition based, so providing they are successful, local authorities can use the grant to procure new vehicles and infrastructure or distribute the funds to operators for ZE procurement.

The ZEBRA grant covers up to 75% of the cost increase from a diesel to a ZE vehicle and infrastructure. While ZEBRA funding is essentially free, local authorities must also allocate funds, and operators have to plan investment from their profit & loss accounts. For example, Leicester City Council, with a total fleet of 414 vehicles, has been awarded nearly £19m (€21.5m), with operators FirstBus and Arriva contributing £25.8m (€29.2m), and the city council providing £2.2m (€2.5m). This £47m (€53.1m) plan aims to provide 96 new electric buses by 2024.

What the sector requires is a commitment around long term funding for zero emission buses and a quicker, more streamlined approach to allocating this funding – the government has funded 2,548 zero emission buses since 2020 – only 130 of these have been ordered and very few are yet on the roads

Confederation of Passenger Transport policy director, Alison Edwards.

“The operator or local authority still has to find 25% incremental cost on buses and infrastructure, and beyond this, additional changes such as remodelling the depot and transitioning maintenance resources are not fundable through ZEBRA, meaning for us a further £8m (€9m) still to fund,” says James Carney, finance & commercial director, Blackpool Transport Services, which has received £19.6m (€22.2m) in ZEBRA funding to procure 115 electric buses and infrastructure.

“Nevertheless, the ZEBRA grant is the opportunity to invest money that wouldn’t otherwise be there. The cost of running electric buses medium term is lower than diesel, so despite the initial investment, it can make financial sense long term”.

Making a business case

For some regions, particularly those with rural routes and lower passenger volume, local stakeholders cannot at present afford to begin the transition, either because local authorities aren’t allocating funds, or operator investment is undesirable for less profitable routes. Higher bus patronage is therefore a crucial requirement to encourage ZE investment.

With 1,724 ZE buses in operation in the UK by October last year amongst a total fleet of 37,800, and approximately half of the UK’s current ZE buses operating in London alone, over 95% of the UK’s vehicles are still to transition. In England, excluding London, the DfT has awarded competition-based grants to local authorities, most recently comprising the Zero Emission Bus Regional Areas (ZEBRA) scheme. This has distributed £270m (€305.4m) in 2021/22 to 17 local authorities, with a further £205m (€232m) to be issued this year.

“We’ve had decades of declining bus patronage and we still haven’t seen a return to pre-Covid passenger numbers,” says Daniel Hayes, programme manager at Zemo Partnership, an independent organisation working closely with government and the UK industry to accelerate transport to ZE. “Diminishing operator profitability is making the transition more challenging, so we’re still seeing sales of Euro VI vehicles.”

Measures to improve occupancy have also been a condition of operator investment.

“In Oxford, our ZEBRA participation was subject to introducing bus priority schemes to increase bus speed by 10%, where decreasing journey time by 1% typically gives an equal increase in passengers,” says Louis Rambaud, group strategy & transformation director, Go-Ahead Group. “These kinds of partnerships allow our business case; it’s limited investment for local authorities and it benefits all stakeholders”.

As ZEBRA has comprised rounds of application and competition for funding at intervals, this has also created uncertainty and a stop-start procurement approach. Tim Griffen, project officer at Zemo Partnership, says: “Operators and local authorities work hard to compete for a share of government funding announced at intervals, then there’s a delay before the money is actually received, then there’s a rush to the manufacturer. And, if the application is unsuccessful, they may not receive any funding. This makes it difficult to plan, especially for manufacturers, so more consistency would be useful”.

“We haven’t yet seen evidence of the effectiveness of the 22p per km and while it accumulates over a 15-year vehicle life, it doesn’t remove the upfront capital cost” says Daniel Hayes, programme manager at Zemo Partnership. “The problem is also that the existing Bus Service Operators’ Grant (BSOG) of 35p per litre of diesel counteracts the ZE incentive”.

With an application process taking six to nine months, the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) also says the funding process needs improvement. “What the sector requires is a commitment around long term funding for zero emission buses and a quicker, more streamlined approach to allocating this funding – the government has funded 2,548 zero emission buses since 2020 – only 130 of these have been ordered and very few are yet on the roads,” says CPT policy director, Alison Edwards.

What about City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements?

An additional funding stream is also available via City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements, open to eight city regions outside of London, delivering £5.7bn (€6.5bn) capital investment in local transport networks. Greater Manchester, for example, has allocated £115m (€130m) to its ZE bus programme with £45m (€51m) committed to deliver 100 electric buses.

Meanwhile, the Levelling up Fund is a £4bn (€4.6bn) government-funded programme to invest in regeneration, culture, and transport schemes across the UK. Unsuccessful in its ZEBRA bid for 73 electric vehicles, Transport North East is applying via this alternative with the aim of delivering 52 electric buses. In a separate scheme, DfT also awarded £50m (€56.3m) to the West Midlands Combined Authority to support the Coventry All Electric Bus City and the introduction of up to 300 electric buses.

As well as grants, the DfT is also offering operators an incentive of £0.22 (€0.25) per kilometre for accredited zero emissions vehicles.

“We haven’t yet seen evidence of the effectiveness of the 22p per km, and while it accumulates over a 15-year vehicle life, it doesn’t remove the upfront capital cost,” says Daniel Hayes. “The problem, however, is that the existing Bus Service Operators’ Grant (BSOG) of 35p per litre of diesel counteracts the ZE incentive. Operators need this funding but it’s acting against the incentive”.

Funding London’s ZE fleet

Transport for London’s (TfL) franchised service now includes over 875 ZE buses. After an initial introductory phase of six electric vehicles, TfL received £3.5m (€3.9m) in early 2019 via the Green Bus Fund, comprising 44% DfT funding with 56% input from TfL itself. TfL says that by improving costs per bus, the budget was able to stretch to 126 vehicles. Over the next decade, TfL also plans to significantly expand its outer London bus network. Currently, the fleet has around 9,300 vehicles with a fully ZE fleet target date of 2034.

Since 2021, all new buses entering TfL’s fleet have been ZE, with all funding after 2019 coming from TfL’s network costs. Fares are the main contributor, typically reaching around £1.5bn (€1.6bn) per year since 2015, partially recovering after Covid to £1.2bn (€1.4bn) last year. Income also derives from road network compliance charges such as London’s Congestion Charge, as well as central and local government grants.

Funding the UK’s devolved administrations

Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have received funding to invest in plans similar to ZEBRA with over 600 zero emission buses funded so far. In Scotland, the ScotZEB scheme launched in 2021 pledged £62m (€70m) to nine operators and local authorities to cover 276 ZE buses and infrastructure, and a £58m (€66m) second phase is expected this year.

A notable investment example includes FirstBus’ introduction of 193 electric buses, the UK’s largest electric bus order outside of London, at its Glasgow Caledonia depot, which is also the UK’s largest electric charging hub.While Scotland has a much smaller fleet than England, ScotZEB has been praised as a faster and more efficient application process than ZEBRA, with less bureaucracy but arguably less scrutiny.

As of October 2022, Scotland had 273 ZE buses in service.The Welsh Government has awarded almost £28m (€32m) in ad hoc ZE bus grant funding to local authorities over the last three years. With the aim of achieving a 50% ZE fleet by 2028, Welsh Government says that fleet transition plans including funding are near completion.

Wales has 68 ZE buses in service.In Northern Ireland, £88m (€99.5m) investment was announced at the end of October last year for 100 EV buses and infrastructure, following £98m (€111m) provided since 2020 for 140 zero emission vehicles. Currently, there are 83 ZE buses in service in Northern Ireland.

More passengers needed

Government grants and incentives are important contributors towards the UK’s ZE transition. However, a self-sustaining approach with a modal shift in consumer behaviour is important to achieve environmental and economic sustainability. “To be in a position to deliver on net zero goals, the focus must be on increasing passenger numbers travelling by bus,” says Alison Edwards. “This will deliver a sustainable model to enable operators to continue reinvesting and deliver a network that is continuously improving”.